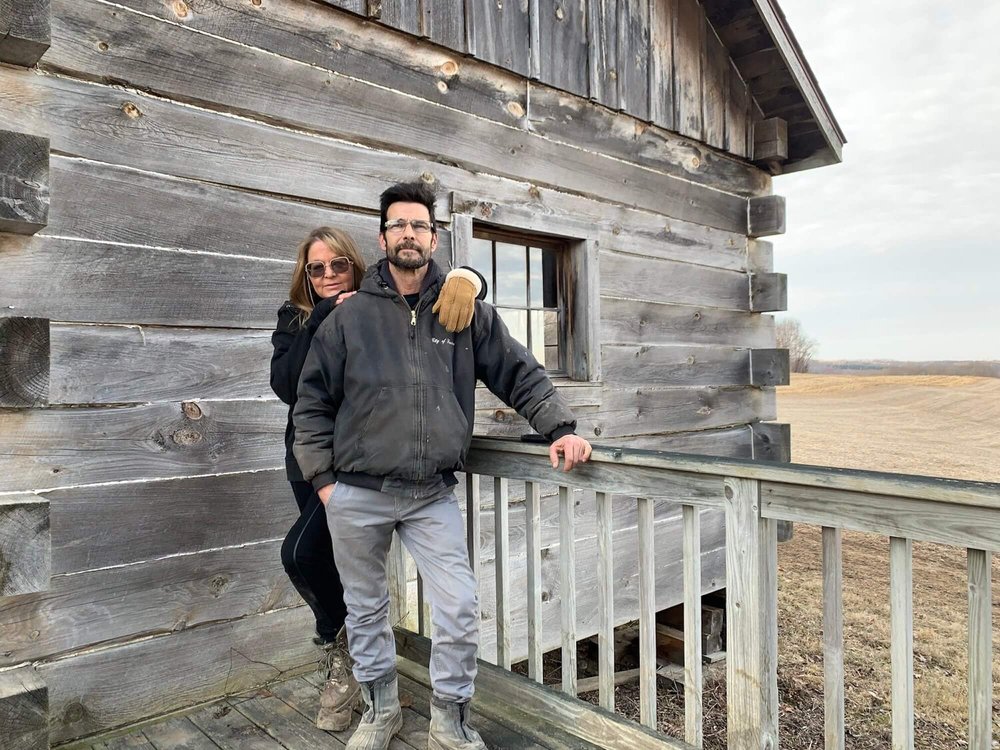

Nicole Porter wants to help save the yak. And she’s come up with an inventive if unorthodox plan to do so: by making yak’s milk cheese. “Yak cheese saves the yak because every piece of cheese makes it possible for farmers to have a reason to breed yaks,” says Porter, co-owner of Prairie Sky in Rolling Hills, Wisconsin. She and her husband, Dan Salvato, import and sell Tibetan-made yak cheese and hope to breed a large enough pure heritage herd at their ranch to have local dairies produce a domestic version.

The Only Yak Cheese in the US

Many in the United States are unfamiliar with yak’s milk cheese. No surprise there. The Salvatos are the exclusive distributors and their foray into crafting yak cheese is in early stages. Because yaks produce only half a gallon of milk daily as compared to the 8-10 gallons produced by a dairy cow it takes a long time to produce the cheese in quantity.

Porter plans to market the cheese as a rare commodity similar to cheese made from moose or donkey milk. It costs between $53-$63 a pound and is available on the Prairie Sky website, at Milkfarm in Los Angeles, CA, Marché in Glen Ellen, CA, and Beautiful Rind in Chicago, IL, and is featured in a dessert at Himalayan Wild Yak in Ashbrun, VA.

Porter describes the cheeses as “pungent, earthy, and nutty,” adding that they take on the flavor of the Tibetan terroir. The milk “is very flowery and medicinal. It flavors the cheese in a unique way,” she says.

That flowery medicinal quality comes through in the creamy, pale golden yellow tomme. The cheddar, a creamy light yellow, is full-bodied with a grassy undertone, and the dense gruyere, a shade paler than the cheddar, has a milder flavor than a traditional gruyere.

Tibetan Terroir & European Style Cheeses

Prairie Sky’s cheese is currently made by a French fromager, Francois Driard, whom Porter made a point of meeting when she gave a presentation on the yak in the Tibetan Plateau. Adding to the cheese’s artisan appeal, the milk is hand bucketed. They chose to produce tomme, cheddar, and Gruyère because those are cheeses that appeal to a Western palate and there are many uses for them, unlike the hard pichuri cheese made of yak milk that the nomads eat.

Preserving Tibetan Culture

Porter and Salvato also want to support the nomads’ traditional way of life and herding. They pay the nomads a living wage by Tibetan standards, buying upfront a year’s worth of the milk that is trekked down weekly on donkeys from the side of Mount Everest to a central processing center similar to a co-op. The nomads live in tents at about 13,000 feet, moving up and down the hill season by season.

The couple was captivated by the yak while visiting friends who raised the purebred, registered, pedigreed variety. “They’re so charming,” enthuses Porter. “These are big, fluffy animals, they look sort of like a {Sesame Street} Snuffleupagus. All of them have nice big horns, and they’re just gorgeous.”

When you get to know a yak,” she continues, “you can see that when they get excited about something like snowfall, they’ll start hopping, jumping, and running across the field with these fluffy tails flying.” She and Salvato appreciate their intelligence and that their herd-like social structures are not quite much more complicated than most ungulates. “We just fell in love with them.”

The pair’s mission came into focus when they started raising yak and discovered the heritage or purebred variety is endangered in the United States. To prevent hoof and mouth disease, yak can’t be imported. Hybrid yaks are mixed with cattle to grow faster and produce more meat, which degrades the biodiversity. The couple got their yak from the rare breeders here whose stock was imported from “bos mutus” or wild yak in Tibet at the turn of the century and have bred to retain that purity.

It seems natural that the duo would connect to these gentle creatures. Porter, an epigeneticist, epidemiologist, and animal behaviorist who holds a Ph.D. in Developmental Psychobiology (now referred to as epigenetics) from DePaul University in conjunction with the Mind and Biology Institute at the University of Chicago, and Salvato, a Chicago city superintendent in Chicago, had been yearning to escape back to nature and had promised her family’s racehorses a place to happily live out their days once retired.

In 2015, they bought an 83-acre ranch on a hilltop in southwestern Wisconsin near the Mississippi and Wisconsin Rivers in what’s known as the Driftless area, a region untouched by glaciers despite three different ice ages.

A Yak Herd in Wisconsin

Porter and Salvato’s herd consists of 3 breeding bulls, 25 cows, and 11 spring calves.

They hope to inspire fellow farmers to follow their lead and to support the struggling dairies that are integral to the local culture by offering yak milk as a production option as they view it as an alternative to dairy milk. Yak milk, says Porter, contains more micronutrients, protein, and omega-3 fatty acids than cow’s milk.

Porter founded the World Heritage Yak Conservancy to research yak genetics, eyeing the potential to save the species in the Himalayas by repopulating them as well as breeding them in the United States. She also wants to educate farmers to properly care for the animal.

Porter and Salvato are in the early stages of producing a domestic cheese. “It’s quite a learning curve this year because they {the yak} make so little milk,” she explains. Birthing calves get the first milk to establish the relationship with their mothers, so not much is left over to experiment with cheese making. A certain amount of yak is required to produce enough milk to scale production. The couple is learning affinage and has a cheese cave in which they can age the imported cheese for 6-12 months and up to three or four years.

Porter appreciates and respects the practical and spiritual roles the yak play in Tibetan culture, underscoring the importance of her desire to preserve the species. The nomads consider the yak part of their family and view them as spirits of nature, similar to how the Native Americans regard elements of the universe.

“Everything – fiber, meat, milk, and cheese – you can imagine comes from yaks,” she says. “It’s their {the nomads’} livelihood in a very profound way, and they live intimately with the animals in a way which we probably don’t quite understand.”

The nomadic lifestyle in the Himalayas and Mongolia is fading, says Porter wistfully, spurring her work to preserve the yak. “It’s such an incredibly beautiful culture. It’s a sort of cultural diversity I think, particularly in the 21st century, that we need to teach ourselves that there are other ways to live other than in concrete blocks.”